Discovering ones beginnings didn’t seem all that important in early life, who has time to think much of the past with so much future ahead. My family tree consisted of a few close relatives that I recall meeting, but little was known or even discussed of an earlier generation. How I wished I had asked more questions of the senior members of my family while they were still here. I had few names, dates or locations but a new invention called the internet began to provide the missing pieces to my genealogy jigsaw puzzle. A few years later, my family tree had grown to more than 500 relatives dating back to the 1700’s. Finding and visiting the final resting place of ancestors in Ohio and Pennsylvania and reading newspaper accounts of their lives more than two hundred years earlier, provided the basis for my early chapters. Don’t expect much more than the story I tell. Perhaps it may bring a smile or remind you of a similar occasion in your own life. I’ll just tell it as I remember it. The peaks and valleys in my life and the struggles in-between varied in size. Many people start out poor and get rich, only to return to being poor. My life fits the scenario of the valley that vaults to a peak and then is pushed back down to a damn valley again. ‘Grandma Rook’ proclaimed it all came from luck. It always seemed to me however that many titans of success became extremely wealthy and created their own luck as they navigated between those peaks and valleys. As I grew up, my mind never relaxed. I could never turn off the engine producing thought’s that raced through my head at night, so I slept with a pencil and pen bedside to capture any ideas I had and the next day I’d read what I left behind from my scrawls. The need to wake up, turn on the light and start writing on a pad finally came to an end with the advent of a small tape recorder I used to collect my late night mumblings. It’s been hard for me to be patient in a world that moved too slowly for my thinking. I often paused to make notes to myself on one of the ever-present legal pads I kept at hand while in the middle of explaining things. In the days before electronic file keeping, a simple pad and pen sufficed. As I tended to any one of my various thoughts, I simply dated them or crossed them off the pad. It took me some time before I trusted computers enough to store my notes in them. I recently discovered legal pads full of scribbles from as far back as thirty years ago in storage. Some photos not previously published from boxes long unopened. Lots of material to feed these pages, now safely inside my computer where I’ll attempt to decipher in these reflections of Passing Thru.

Chapter One My Arrival and Beginnings

Five thirty in the afternoon was the time I decided to arrive in the world in Chillicothe, Ohio on an October day. While my mother Gladys brought me into the world, my father Gordon worked. His day time employment as a truck driver was supplemented by a new job at an all night gasoline station and felt asking for time off to attend my birth could risk his employment. The hills of southern Ohio always greeted one with a constant stench from the local paper mill and the foul smell took some getting used to. This part of the country had become home to those who wanted to escape the coalmines of West Virginia and overflowing unemployment lines. Hundreds of miners were dying each year and John L. Lewis, the leader of the coal miners union, strived to deliver a livable wage and safer jobs for those who dared to take a coal car into the dark bowels of the earth. We were poor and lived in a poor town at a poor time in the history of a country that was waking from a long bad dream. The Great Depression wasn’t far removed and many families only support came from a paycheck from the WPA (Work Project Administration). Created by the federal government to build highways, the WPA was part of President Franklin Roosevelt’s plan to help solve some of the nation’s unemployment and help dig the nation out of the depression.

To feed a family of four dad worked various jobs, including tending to the occasional customer in the dead of night at a gas station. Our rent was forty-two dollars a month for three rooms on the second floor of the Lumbeck apartments located at the edge of the downtown area with the Sciota River nearby. Dad rarely earned over one hundred dollars a month so things were tight. The average yearly wage was $1,250, a loaf of bread was 9 cents, a gallon of milk delivered to our door was 25 cents, a gallon of gas cost a dime. During times when food was scarce, my brother and I were sent to stay with our maternal grandmother. Susie Milliken, or ‘Nanny’ as we called her, was a single-mother who supported her brood of seven after my grandfather, John Milliken, bled to death from a tooth extraction at the age of 28. As if the depression wasn’t enough, the family also lost all of their belongings in a house fire. We looked forward to visiting her in Coalton, Ohio, another small town buried in the hills of southern Ohio. During times in Nanny’s care, she took us to the country to Grandma Downard’s, where milk from the cows was plentiful and fried chicken seemed to always be abundant. I loved bathing in Nanny’s large galvanized washtub where she also laundered our diapers and clothing. Water heaters were still in the future as several kettles of water heated on the large cast iron wood stove warmed our bath. The trips to Coalton included time spent with those aunts and uncles who were not away fighting a war and I always cried when time came to return to our little three-room apartment in Chillicothe. My grandparents, Claude and Hannah Rook, migrated to Ohio from Williamsport, Pennsylvania after first living on the Pine Ridge Indian reservation in South Dakota. My grandfather taught reading, writing and arithmetic to these Native Americans at the turn of the century and my grandparents were among the first white people to live on a reservation with the Sioux. Hannah served as a nurse to a people steeped in poverty and poor health. Alcoholism and sickness was rampant and life was very harsh for all who lived there. Most of the Sioux were

homeless or crowded into teepees and Grandma Rook often tended to the sick in the warmth of the pioneer home made of mud and straw that was built into the side of a hill. At first the Sioux were very suspicious of my grandparents. The name Rook sounded too much like Crook, the name of a U.S. Army general the Sioux held responsible for the stabbing death of Chief Crazy Horse at nearby Fort Robinson, Nebraska. After she proved her “magic” medicines were beneficial to the tribe, some of the Sioux became quite close and actually gifted Hannah with head dresses, war bonnets and items that her grandson Max would bequeathed to a museum in Maryland. Prior to World War II, women were relegated to cooking and raising children, very few contributed income to the family’s well being. We looked forward to the arrival of Hannah in those days. She climbed the stairs to our apartment with her hands full of fresh vegetables from her garden and food she had canned at her house across town. Grandpa Claude would wait in his 1933 Desoto while grandma unloaded the goods in her arms into a kitchen cupboard and the “icebox,” a two-door chest that held food in the bottom and large chucks of ice on the top shelf. The door to our apartment was never locked and deliveries took place with a shout of “Milkman!” or “Iceman!” Refrigeration had not yet arrived at our home and twice a week the iceman would lug huge chunks of ice up the steps. The milkman, who delivered large glass bottles of milk, usually followed sometime later, and one could see the rich cream firmly settled on top in the bottles. Homogenized milk wasn’t an option. I remember going with my grandma to her friend Hattie’s house on Carlyle Hill, “Where the rich people live,” to see Hattie’s new ‘Shelvadoor’ refrigerator. They stood and marveled not only at the refrigerator, but also because it actually had shelves in the door. It wouldn’t be long before grandma’s constant harping to grandpa finally resulted in a new Shelvadoor being proudly displayed in her home too. When we were actually allowed to open the refrigerator, she always cautioned us not to slam it because it could damage the seal on the door. Coming from an era where cold food storage was previously provided by root cellars dug into the side of hills, she was most protective of her new treasured modern appliance.

John & Charles Rook 1939

Dorothy “Dottie” Rook 1943

Three years after my birth, sister Dorothy (Dottie) joined Charles and I, adding another mouth to feed, and the three of us in just one crib. Mom felt fortunate finding a job washing dishes at a tavern across the street, and with dad at work Grandma Rook arrived to watch over us. We begged to go home with her, where we could sit in excitement on the floor in front of a big Zenith cabinet radio listening to the ‘Grand Ole Opry’ live on WSM from Nashville on Saturday nights. Roy Acuff & the Smokey Mountain Boys brought the ‘Wabash Cannonball’ into our living room and Bill Monroe’s Kentucky blue grass music prompted Grandpa Rook to bring out his banjo from a cloth case, where he joined in “picking away” with Mother Maybelle Carter’s “Wildwood Flower”. Minnie Pearl, a female comedian, delivered humor during the war years of the early 1940’s starting with her trademark screeching introduction, “How-dee, I’m just so proud to be here”. Country music was the only music in my early life, with the exception of the religious hymns of our Methodist faith. Escaping the poverty of West Virginia, Kentucky and Tennessee, “hillbillies” had moved north to southern Ohio and brought their music with them. “The Nations Station,” WLW in Cincinnati was allowed to broadcast for a short time with 500,000 watts as an experiment afforded by the Federal Communications Commission. Bing Crosby’s brother’s Bob and his Bobcats, along with Rosemary and Gayle Clooney were also regulars on WLW. The singing talent of another local, Doris Day, would catapult her into the movies. The experimental super power of WLW didn’t last long. Disgusted, Grandpa Rook grumbled Crosley couldn’t afford the increased electric bill of a superpower WLW because he was going broke making cars no one wanted. Powell Crosley had just introduced the first mini-sized American made automobile. For the first time, two new buzzwords entered our automotive vocabulary – “miniature” and “bantam.” The ‘Crosley’ was a foot shorter and one hundred pounds lighter than the Volkswagen Beetle that would come later. With an $800 sticker price, Crosley was unable to convince consumers to purchase his miniature car when a full-size automobile was only a few hundred dollars more. In the years ahead, Packard, Hudson, Desoto, Kaiser, Studebaker and others would join Crosley in the graveyard of American automobile makers. “Crosley’s got too many irons in the fire,” said my grandfather. He marveled at the new technology of refrigerators, radio and even cars, but not one “the size of a damn roller skate.” Claude always preferred a “man sized carriage” like a Chrysler or Desoto. American automobile manufacturers soon were working overtime building the war machine’s needed to defeat those “Damn Germans” or “Damn Jap’s” as our nation entered the war pitting us against the Axis of Japan, German and Italy. An educator and man of considerable intelligence, Grandpa Claude Rook often dressed in his dark blue three-piece suite. Even when he sat in the living room reading the day’s newspaper, his attire was formal. Only during times when he changed into his “yard clothes” was I permitted to hang on to him as he got down on all fours on the living room floor and became “the bear,” which made me and my cousin Max squeal in delight ridding on his back. During winter months when the sun set earlier, we could pick up WSM in Nashville and the ‘Grand Ol’ Opry’ clear as a bell. On one summer evening though, grandpa frowned in discontent as he tried to pick up the “Opry” through the static of a nighttime storm. The annoyance of static didn’t effect his own high-pitched voice joining Roy Acuff and the Smokey Mountain Boys. To my young ears he sounded great and I’d often sing along to songs like “Turn the Radio On,” “Mule Skinner Blues,” or “How Many Biscuit’s Can You Eat This Morning…This Evening…This Night.” WLS in Chicago (which was then owned by Sears Roebuck and Company and whose call letters stood for “World’s Largest Store”) brought us the ‘National Barn Dance with Gene Autry’ who’s “Silver Haired Daddy of Mine” became a favorite of my father. He attempted to duplicate the singing cowboy while strumming a guitar he received as payment for a job he had done. Who would have guessed I would someday captain the station that introduced me to Captain Stubby and the Buccaneers, LuLu Belle & Scotty, and The Hoosier Hotshots with their washboard musical magic? The Hotshots coined the expression “Are you ready Hezzie?,” a common question of the day I used over and over until I was ordered to stop. Captain Stubby and George Goebel reached stardom on the ‘National Barn Dance’ and I met them both in the years ahead. KDKA in Pittsburgh and KWKH in Shreveport were also featured on the radio dial of grandpa’s big Zenith mahogany cabinet radio. “Shushing” us to be quiet, he tuned in to Walter Winchell, whose words “Good evening Mr. and Mrs. America and all the ships at sea” began each broadcast. The news of the day was also brought to us by H.V. Kaltenborn, Gabriel Heater, Edward R. Murrow and Lowell Thomas, who always signaled our “quite time” would end with his “So long until tomorrow.” Our President, Franklin D. Roosevelt, was a father-like figure and his famous fireside chats were especially welcomed into families’ living rooms where most radios were located. Everyone listened carefully, not to miss a word. One of the first songs I remember singing was “Mare Zee Doats.” I sang those silly words, “Mares eat oats and does eat oats and little lambs eat ivy” until someone place a hand over my mouth to end the silly serenade. I stationed myself at Grandpa Claude’s feet not to far from the radio to hear Joe Louis defend his world heavyweight championship against foe after foe. Little did I know then that one day in the future I would actually meet the “Brown Bomber.” I shook his hand as he welcomed me at a Las Vegas hotel later on, a great champion reduced to being a doorman at a time when he should have been living in comfort was a sad sight.

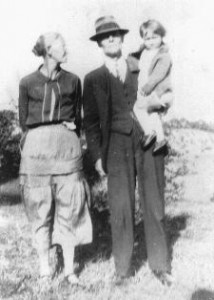

Gladys, Gordon, John & Charles Rook 1939

As a student, my father and his brothers were very popular as athletic stars, his adjustment to fatherhood was a rude introduction to a totally different life. He no longer heard the cheering of fans and fatherhood wasn’t a welcome responsibility. Charles followed in his fathers footsteps in high school but Dottie and I were not afforded the same treatment. Probably because he was the first born, Charles could do no wrong. Dad regularly reminded Dottie and me, “You’re just like your damn mother.” Early on I developed a lisp that disappeared years later when a speech therapist blamed it on insecurities in my youth. It was an equal embarrassment to dad who made fun of my speech impediment, calling it “baby talk.” My discipline came from shout and shove, Charles never needed correction. My older cousin Max Byrkit was more like a brother and would remain so throughout our lives. Max would become a well known, highly respected medical doctor in the Hagerstown/Williamsport, Maryland community. After three children in a row our mother Gladys filed for divorce and I was sent to live with my grandparents, Claude and Hannah. Sister Dorothy, or Dottie as we called her, vanished and I found out later she was living with mother at Grandma Milliken’s in Coalton, Ohio. Charles continued to live with dad and from time to time they visited me. Grandma Rook, a devout Christian, warmly provided an ingredient missing in my early life. I didn’t understand why tears streamed down her face on that cold December day in 1941 when the somber tone and words spoken by President Roosevelt on the radio told us our nation had been attacked by Japan and thousands of young sailors had died at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii. “Hear! Hear!” grunted grandpa in agreement to what President Roosevelt called, “a day that would live in infamy”. Leaning closer to the speaker of the big Zenith to hear every word, it was suddenly clear to me something terrible had happened. Grandma Rook’s tears triggered my own as I ran and hid under the wooden back steps of the house where I crouched in fear of what must be coming. Realizing my absence, Grandma Rook came to the back door calling my name, “Johnny! Oh Johnny!” until I flew into to the safety of her arms and she wiped away the tears I cried. She carried me back into the house, through the kitchen and the living room, past grandpa still glued to the radio, to the front porch where we sat for several minutes before suddenly, one by one, young men from every family emerged from the front doors of the homes all around us. These young men, the best our nation had to offer, gathered briefly to talk among themselves before they piled into cars and headed toward the county court house to enlist as warriors to “fight the dirty Jap’s.” Within days, only women, children, elders, and aged grandparents were left in town. Almost all able-bodied young men were gone. My uncles enlisted and soon found themselves shipped overseas to join the war effort. Several of my aunts gained employment in manufacturing munitions and equipment needed by the military. Women joined the Army and the Air Force as WAC’s (Women’s Army Corps) and WASPs (Women’s Armed Services Personnel). Still more joined the battle as WAVES and SPARS, the female branch of the Navy and Coast Guard. Grandpa Rook, who frowned when he saw them, scorned the few able-bodied young men left in town chastising them as cowards. Grandma scolded him reminding of his own son, my father, who was exempted, claiming three children to support. I also recall a discussion between my grandparents concerning the use of “niggers” in our military. Grandma Rook thought it was a good idea, but Grandpa Rook quizzed, “What could they do?” and cautioned against mixing them with “our guys.” Segregation was an accepted norm in America as Negroes kept to their own part of town and were seldom seen on the streets of Chillicothe. The sudden appearance of a person of color, was noted by grandpa Rook, “Lookout Johnny, here comes a dark cloud.” Children sometimes created games to reflect the country’s conflict with our enemies. My childhood friends Russell and his sister Ruthie took their revenge on the ‘Jap’s’ by setting fire to a cardboard box filled with paper and watching as “Tojo’s house” burned. My grandmother scolded us, reminding newspapers and boxes were to be saved for paper drives in the war effort. Grandma was a strong woman with strong convictions and she complained when she learned many of the female casualties returning home in caskets did not receive a military funeral. She joined the ladies of her lodge, the Eastern Star, and they made their feelings known in a petition sent to FDR’s White House. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt sent back a letter in agreement, and soon women killed in the line of duty were also honored. The honors were still not really equal to those afforded to the men who gave their lives in defense of the nation, but it was a start in getting these women recognition. Short on manpower, American industry had to rely on women to take jobs previously handled by men. Automobile manufacturers stopped making cars and instead began building jeeps, tanks and other war machines. My aunts accepted jobs in various factories to supplement the limited dollars being sent home by my uncles serving on the front lines of battle. My father, separated from my mother, claimed three kids and a wife to support, and that exempted him from military service. He was soon employed as an electrician at Wright Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio, where the daily commute of two hours would seriously limit his time at home. This allowed Charles to spend more time with me and my grandparents. President Roosevelt encouraged us to replace lawns and empty spaces with “victory gardens” and to save tin foil from chewing gum and cigarette packages for the war effort. Families received ration stamps from the government each month needed to purchase various foods. Another special stamp and an additional nineteen cents a gallon were required for gasoline. Other efforts to limit the use of gasoline and save on tire wear-and-tear included enforcing speed limits of forty miles an hour on most highways. Cigarettes, not yet known as harmful and popular, were rationed to provide nerve calming “fags” for our servicemen and women. It took a month or more for a letter to find its way to a serviceman halfway around the world in a far off foxhole, but it was delivered for the mere cost of a three-cent stamp. For those who could not afford the stamp, penny post cards carried messages from home. A photo of loved ones was a welcome sight to a soldier gone for long periods of time. On those rare occasions when letters were received in return, families hurried about the neighborhood sharing the news with each other. Telephone calls home were in mostly non-existent to those stationed overseas. Months went by before many servicemen stationed overseas were heard from via a quick scribbled message. Government censors made sure information considered detrimental to our troops would not find its way to the enemy. “Loose lip’s sink ships” was the motto and it served as a reminder - information about the war was not to be discussed, least it wind up in the hands of the enemy.

Charles, uncle Clay, Dottie & John Rook 1942

Since manufacturers changed all efforts to supplying the country’s military needs, Christmas gifts for children were limited to previously used toys collected by the Salvation Army and passed out to each lucky child that received one. Popcorn balls and apples were stuffed in Christmas stockings and while we had a Christmas tree, no decorative lights were available for those that burned out. Except for Christmas Eve, when children sat and stared at the few gifts wrapped under the tree in anticipation of opening them the next morning, lighting was restricted. Outside lighting was unheard of, far too extravagant, and wasteful of the precious electricity the country needed. Those living on the nation’s coastal areas had to use blinds and heavy curtains on windows to block any light that escaped because it could serve as a beacon for a possible attack from air by the enemy. Boy Scouts regularly held drives for any materials that could be recycled into much needed products for the war. They would pick up scrap metal, paper, rubber, at curbside, and friends and strangers alike admonished anyone caught wasting such valuable resources. Once each month, Grandma Rook held my hand while we stood in line at the meat market or the grocery store and counted our precious rationing stamps to see if we had enough for the goods we needed. We were lucky enough to get what we could as supplies were scarce. Sugar, butter and meat were rationed heavily, and soon in many back yards screened areas were constructed where chickens were raised to produce eggs and meat. A good sitting hen was valuable for her hatching ability, but woe was the fate of the hen that didn’t lay eggs or the chick that had hopes of becoming a rooster. Only one “king” was needed for a hen house, others wound up being the featured part of a good Sunday dinner. We also scoured fields nearby in search of dandelion greens for use in salads or cooked in place of spinach. Rhubarbs, apples, peaches, squash, cherries and berries came from our back yard and as winter approached, neighborhood ladies gathered on weekends to can fruits and vegetables in glass jars sealed with a waxy substance called paraffin. Sweat poured from their brows while they cooked and canned the family provisions before carrying them to basement shelves where they were stored for later use. Empty lots in the neighborhood became victory gardens where women and elderly men worked tirelessly raising corn, peas, beets, tomatoes and potatoes. The war machine needed tin and grocery shelves were limited to dry goods such as beans, bread and oatmeal. Some meat markets had “cool rooms” for the preservation of meat, but most foods had to be either eaten or canned on the same day they became available or they spoiled. The taste of candy was always a real treat to young children, but with sugar rationed, the opportunities for satisfying that taste were rare in those days. I remember the day I discovered a canister of shredded coconut in Mommy Rook’s pantry and how much it fed my need for sweets. While she talked to the postman at the front door I quickly carried my prize to my favorite hiding place under the back steps of the house and began to gulp down the coconut as fast as possible. Within minutes I became very ill and garnered the attention of my grandmother. Being spanked would have been a welcome penalty; instead she demanded I drink a mixture of baking soda in a glass of water. I recovered a few hours later and promised myself I would never allow coconut to pass through my lips again. Uncle John Moore was given a purple heart for service he gave to his country as a US marine in world war II. My step mother, Della was so glad to see him crutches and all. “War Mothers,” those who had sons fighting Hitler, Mussolini or Tojo, displayed a flag and a small star that represented each loved one serving in the military. These badges of honor hung in the front windows of almost every neighborhood home and one lady received great admiration when she proudly displayed six stars on her flag. Sadness gripped us all when three of her sons were killed in battle in the first year of the war. I remember the first time I saw airplanes flying in formation; I stared up at the sky, counted them and wondered where they were headed, until they vanished from my sight I did not understand the meaning of the word ‘divorce,’ but I remember Grandma Rook used it often when she explained to friends why I was no longer living with my parents. Sitting with her on a bench outside the courtroom, I became frightened when suddenly mother Gladys appeared. She broke into tears as she rushed to me, pulled me from my grandma’s grasp and started to hug and kiss me. I broke into tears as well and Grandma Rook carried me out to the car and with grandpa at the wheel, they took me to their house. I was sure I’d never see my mother again. In fact, I would when I was a teenager. Hannah & Claude Rook 1950 Grandma Rook took me with her when she volunteered at a nearby orphanage. There she cleaned, laundered, cooked and cared for the children dropped off during hard times by parents or relatives unable to provide for them any longer. With grandma busy, I was included in the activities of the orphanage’s residents and I began to feel more and more accepted as I played, ate and took the compulsory afternoon naps with other children. At the orphanage I had my first experience with “Negroes,” when several black children demanded I surrender my lunch to them each day. They picked through my lunch led by their much older leader, Reggie Johnson, who delighted in bending my arm behind my back until I grimaced in pain and my eyes evidenced fear. My abuse fed Reggie’s daily need to bully someone and my lisp was a favorite target for his ridicule. Not wanting to be taken to this dungeon of terror anymore, I finally begged to stay at home. My grandmother dug for clues as to why and finally I half-heartedly explained the fear I had of Reggie. A few weeks later Reggie was taken into custody for beating up the son of a local merchant who had notified authorities. Minus their leader, his gang soon disbanded and I no longer felt threatened at the orphanage. Several months passed before my father arrived to take me for a ride. As I wondered where we were going, Grandma Rook hurried to gather my clothes in a large paper bag. We traveled silently for several miles, Charles and I in the back seat, before dad stopped to add another passenger with the surprise announcement, “Kids, I want you to say hello to your new mother.” I stared meekly at this stranger who smiled and offered her greeting as we proceeded to our new home, located not more than a dozen blocks from my grandparents. Within days of our introduction, I came upon our stepmother, Della, butcher knife in hand, whacking the heads off chickens as they flopped all over the backyard until dead. She explained this was a necessary part of preparing them for dinner, but it tapered my a taste for fried chicken for some time in the future. Eggs were gathered daily from the hen house and placed in a large bowl on the kitchen table. Without refrigeration, we hard-boiled several each day for eating at a later time. Some eggs were placed in a nest for a hen to sit on and hatch, as we always had to replenish the flock. Most often, chicken was our only meat except for an occasional rabbit or squirrel. It was a confusing time for me. My sister Dottie was gone, I had a change in mothers, and visits to my grandparents were rare. My father met any mention of Dottie or mother Gladys with rage. Trying to comfort me, mother Della talked about Dottie and my natural mother Gladys, but she cautioned me to not mention them within earshot of my father for fear of upsetting him. Della finally persuaded dad to allow limited visits from Dottie, and on those occasions I erupted in joy, ran and played nonstop with her until called for dinner at sundown. One such reunion resulted in my sister falling on a glass hotbed used to germinate seedlings. The cross shaped wound became Dottie’s “airplane” as it scarred her knee. Most of my clothes were “hand me downs” from my older brother so I relished any clothing that came from my Milliken kin. Occasionally, Grandma Susie Milliken sent clothing for me she made herself, but my favorite outfit which consisted of dark brown knickers worn with knee length stockings, came from the Salvation Army. I looked forward to wearing the outfit on my first day at school. Della held my hand in support as we walked to the school. In preparation for this event, she tried to convince me how much fun it was going to be meeting new friends, having new experiences and how much I would like my first grade teacher, Mrs. Larson. As we approached the classroom, she leaned down, gave me a hug and said she would be waiting for me when school let out. As I entered the classroom, I was immediately struck with fear as I recognized my old nemesis Reggie Johnson seated in the back, glaring at me. I took a seat in the front near Mrs. Larson and sat paralyzed in anticipation of what was in store for me. I didn’t hear a word she was saying until we were dismissed for recess. I hurried into the hall looking for stepmother Della and realized she was not waiting for me as promised earlier. In panic, I tried to rush back into the classroom and the safety of the teacher, but Reggie met me at the doorway. More than a foot taller than me, he crashed into me and I fell. I crashed into the door then fell to the floor and I tore my favorite knickers. Mrs. Larson, who witnessed it all, came to my rescue and helped me up. She demanded Reggie, who was smiling, explain his actions. She quickly rejected his story that it my fault for running into him and as she checked to see if I was okay, she led Reggie toward the principal’s office. Della was called to come and get me and after she heard the story of my previous problems with Reggie, she notified Mrs. Larson. Mrs. Larson suggested I stay home for a few days until a solution could be found and when I returned to school, I learned Reggie had been transferred to another school. Within a few days of starting school, Mrs. Larson noticed I strained to see the blackboard and suggested to Della I get an eye exam. The results clearly indicated my need for glasses, but guided by our lack of money several months went by before I finally got them. As luck would have it, I fell and broke the lens on one side and bent the glasses’ wire frame while I played during a recess sometime later. Dad was furious and vowed it would be some time before I could have them replaced. The rest of the school year and the through the second grade, I had to close one eye and use the one good lens on my glasses to see the blackboard. After I entered third grade I finally got a new pair of glasses. The local Eagles lodge heard about my needing glasses from Mrs. Larson so they got me a pair. I proudly thanked her and she beamed with joy seeing me with new “eyes.” My grades improved to a ‘C’ level but my lisp got worse and brought with it more taunting from classmates and my father at home. Before I was seven, I had walked or played all over Chillicothe, and I knew always to return home in time for supper. During summer months, it was not unusual for me to be gone from morning until early evening. Adults were trusted and respected by my generation and police officers were given a place of honor in all our minds. When parents weren’t around to offer guidance, a neighbor or even an adult stranger corrected children or acted as a surrogate parent. Parents actually thanked each other for taking the best interests of their children in hand. With the exception of grandpa’s sparse use of the word ‘damn,’ profanity was not uttered in a child’s presence and taking the Lord’s name in vain was totally taboo. I recall the first time I heard the word “bastard.” A neighbor had “takin’ in too much of the devil’s brew,” according to my grandmother, and after he swore loudly from his own front porch, the police responded and he was taken to jail. The memory of seeing him arrested for swearing stayed with me for many years. On Sundays Grandpa and Grandma Rook took me to the Walnut Street Methodist Church in downtown Chillicothe and I was proud as I sat between them on the big wooden pews. It was worth sitting through the long sermons because I had Mommy Rook’s arm around my shoulders the whole time. As the message of the minister ended, I’d stand to join my grandmother. As she sang ‘Rock of Ages’ and ‘Holy, Holy, Holy’ with me, I’d turn to glance up at grandpa who smiled and winked in approval. This introduction to religion stayed with me for the rest of my life, and from time to time it actually allowed me to consider becoming a minister, like great grandpa Milliken was. Grandpa Rook was a long time member of the local Masonic lodge. My memories of him parading through the living room on his way to a lodge meeting dressed in his Knights Templer uniform, plumed headgear, and sword at this side, impressed me as small boy. I was convinced grandpa was a member of the ruling elite when he told me President George Washington was among his “brothers” in the lodge. jr All Content on this Web site © 2008 John H. Rook All Rights Reserved The opinions & commentary posted on this website are those of John Rook, unless otherwise noted